|

Redding's

Scenic Road Ordinance was adopted and became effective in

January 1986, the first in the region. Since that time sixteen

local roads have received Scenic Road designation. These scenic

and rural roads extend for over 18 miles throughout the town

and typify Redding's picturesque charm and character.

In

the words of John Mitchell, author of the 1984 Open Space

Plan, they are:

"pieces of the frame we call our country atmosphere.

We must find a way to preserve them."

If

you would like additional information about the Town's Scenic

Road ordinance please visit: ScenicRoadOrdandWalls.pdf

for the full text of the Scenic Road Ordinance and Stone Wall

Addendum.

Cross

Highway: From Hill Road (Rt. 107) to approximately 700

feet easterly of Newtown Turnpike; Boy's Club property line.

Length in miles of scenic section: 1.9 miles. Date approved:

8 Apr 1997. Scenic Features: Hills and valley, meadows, mature

trees, historic buildings, distant views.

John

Read Road: From Lonetown Road (Rt. 107) to Black Rock

Tpk.(Rt.58). Length in miles of scenic section: 1.08 (entire

road). Date approved: 22 May 1990. Scenic Features: Upland

terrain, meadows, stone walls, woodland, dirt road.

Lee

Lane: From Redding Road (Rt. 107) to end. Length in miles

of scenic section: .32 (entire road). Date approved: 10 May

1988. Scenic Features: Gentle terrain, mature trees, narrow

winding road.

Limekiln

Road: From Redding Road (Rt. 53) to Lonetown Road. Length

in miles of scenic section: 1.7 (entire road). Date approved:

10 May 1988. Scenic

Features: Valley to rugged upland, woodland, distant views,

winding road.

Marchant

Road: From Simpaug Turnpike to Umpawaug Road. Length in

miles of scenic section: 1.8 (entire road). Date approved:

9 Aug 1988. Scenic Features: gentle terrain, meadows, stone

walls, mature trees.

Mark

Twain Lane: From Diamond Hill Road to end. Length in miles

of scenic section: .25 (entire road). Date approved: 22 Oct

1996. Scenic Features: upland slope, stone walls, meadows,

mature trees narrow road.

Old

Hattertown Road: From Poverty Hollow Road to Newtown Town

Line. Length in miles of scenic section: .43 (entire road).

Date approved: 22 Mar 1988. Scenic Features: broad valley,

meadows, woods, winding dirt road

Pine

Tree Road: From Black Rock Turnpike (Rt. 58) to Easton

Town Line. Length in miles of scenic section: .65 (entire

road). Date approved: 8 Aug 1997. Scenic Features: narrow

stream valley, rushing brook, wooded hillsides, narrow road.

Poverty

Hollow Road: From 500 feet south of Stepney Road intersection

to Newtown Town Line. Length in miles of scenic section: 1.94.

Date approved: 12 Sep 1989. Scenic Features: valley terrain,

rushing stream, ponds, waterfalls, meadow forest.

Sherman

Turnpike: From Newtown Turnpike to Sanfordtown Road. Length

in miles of scenic section: 1.0 (entire road). Date approved:

10 May 1988. Scenic Features: valley to hilltop, steep hillsides,

woodland, narrow partly-dirt road.

Side

Cut Road: From Simpaug Turnpike and Long Ridge Road to

Redding Road (Rt. 53). Length in miles of scenic section:

.67 (entire road). Date approved: 13 May 1997. Scenic Features:

broad valley, mature trees, stream.

Station

Road: From Umpawaug Road to Side Cut Road. Length in miles

of scenic section: .44 (entire road). Date approved: 10 Mar

2009. Scenic Features: gentle terrain, stone walls, woodland,

stream, mature trees, narrow.

Topstone

Road: From Chestnut Woods Road to Umpawaug Road. Length

in miles of scenic section: .96. Date approved: 26 Aug 1986.

Scenic Features: rolling terrain, woodland, meadows, mature

trees, dirt road.

Umpawaug

Road: From Redding Road (Rt. 107) to Redding Road (Rt.

53). Length in miles of scenic section: 3.5 (entire road).

Date approved: 22 Jan 2002. Scenic Features: steep hillsides,

hilltop, upland terrain, woodland, winding road.

Wayside

Lane: From Redding Road (Rt. 107) to fork and thence on

both branches to Umpawaug Road. Length in miles of scenic

section: .82 (entire road). Date approved: 10 May 1988. Scenic

Features: ledgy terrain, woodland, stone walls, narrow winding

roads.

Whortleberry

Road: From Gallows Hill Road to Limekiln Road. Length

in miles of scenic section: .80 (entire road). Date approved:

25 Nov 1986. Scenic Features: ledgy upland terrain, woodland,

narrow winding partly-dirt road.

PREPARED

BY THE REDDING PLANNING COMMISSION 2009

A

special thank you to Jerry Sarnelli for forwarding this updated

material!

I

promise to add photos in the near future.

---------------------------------------------

"The

Roads of Easton and Redding: Their Origins" by Daniel

Cruson

Understanding

the development of towns such as Easton and Redding, as well

as understanding the modern interactions between areas within

these towns and between the towns themselves, can only occur

when the pattern of roads which govern this development and

these interactions is known and understood. In any town, the

road pattern is usually determined as the town is first settled.

This pattern will then be modified as the town grows but through

all of its modifications the basic pattern of roads which

emerges with the first settlers remains. Even today, after

paving, widening and cutting through new roads to give access

to old farm property for subdivisional housing, the basic

patterns established by the crude roadways which were first

cut through the wilderness of northem Fairfield can be seen

by simply glancing a map of Easton and Redding provided one

knows a little of the background of this early road development.

To

understand the basic pattem of roads in the Easton-Redding

area it is first necessary to go back and consider the way

in which the land that would later become these towns was

acquired, divided among Fairfield's proprietor's, and then

settled. The land that became Easton, Weston, and the southern

half of Redding was formally purchased from the local Indians

on January 19,1671 for "36 pounds sterling of cloth valued

at 10 shillings a yard" (i.e. 72 yards of cloth.) Fairfield

had already secured possession of the coastal lands from Black

Rock harbor to the Saugatuck River in what is today Westport,

and extending six miles inland. The Northern Purchase of 1671

, then, gave the town possession of another six miles further

inland so that the town now extended from the coast northwesterly

to an east-west line that coincides with modern Cross Highway

in Redding.

With

a weeks of its purchase, this northem land was divided among

the town's proprietors. This reflected a strong desire on

the part of the town to get all common lands into private

hands quickly and thereby strengthen the town's claims of

ownership over the potential claims of other local Indians

who may have felt entitled to land in this area. In fact,

the Indian John Wampus in 1671 did step forward and try to

claim a substantial parcel of land in Aspetuck. He claimed

this land was his by right of his marriage to the daughter

of Romanock, the chief sachem of the Aspetuck Indians, from

whom she inherited the title of the land at his death ten

years before. After a long and very involved period of legal

maneuvering, the courts awarded the land to the proprietors

to whom it had been distributed for they were in possession

of the land and living on it, whereas Wampus had never actually

taken possession of it.

The

proprietors of Fairfield were those people who were either

the first settlers of the town or descendants of the first

settlers who were entitled to take ownership of a share of

common land as it was divided. A problem accompanied the division

was the land to be equitably divided? This did not mean that

each proprietor was to receive an equal amount of land, for

Proprietors were not equals. Some were far wealthier and,

by the later half of the 17th century owned more land than

others. To these wealthy Proprietors would go the largest

parcels of land. The problem, rather, was to insure that regardless

of its size, no individual would be left with land of poor

quality for farming while another proprietor would end up

with fertile productive land, in addition, the division must

insure against one proprietor receiving land that was tucked

into quality for farming while another proprietor would end

up with fertile productive land. In addition, the division

must insure against one proprietor receiving land that was

tucked into a remote northern region while another received

land that was readily accessible in the southem portion of

the purchase.

The

answer to these distributional problems was the "long

lot". Town officials first began carving up the Northern

Purchase by setting off a strip of land 1/2 mile wide and

which ran across the town from East to West about two miles

above the village of Fairfield. Perpendicular to this Half

Mile Common another strip of land was set off which was one

mile wide and which ran from what is today the green in the

center of Redding, south to the Half Mile Common. This

was appropriately called Mile Common. To either side of the

Mile Common long lots were laid out. These lots were long,

thin stripes of land that ran from the Half Mile Common nine

mile north to the towns northern boundary. They varied in

width from 50 to over 850 feet, the widest lots being given

to the wealthiest and thus more deserving proprietors. Although

their width varied considerably, most of these lots averaged

about 490 acres.

The

long lots were not immediately settled but rather were held

for speculation, either hoping that the land would increase

in value in the future or that it could be given to the proprietor's

sons so that when they came of age they could establish farms

of their own. Land records indicate that these lots were also

frequently sold or traded between proprietors. Regardless,

historians such as Thomas Farnham who have extensively studied

this area, doubt that there was any settlement on these lots

before 1725. This did not mean that the proprietors completely

ignored their holdings to the north, for as soon as land division

is made, concern was expressed over access to the northern

properties and plans for roads were drawn up.

A

year after the 1671 land division a highway was laid out running

East and West of the Half Mile Common. This road assured owners

that they could gain access to the bottom or southern portion

of their long lot. This road survives and is appropriately

called Long Lots Rd. in Westport. Looking at a modern map

of the Westport-Fairfield area, it is easy to see that Long

Lots Rd. forms a straight line east to west, and that Hulls

Farm Rd. and Fairfield Woods Rd. form eastern extensions of

this line. All three of these roads along with several other

shorter ones were at one time connected and formed the northern

boundary between the Half Mile Common and the southern terminus

of the long lots.

Marking

boundaries with roads was a common colonial practice. Modern

Park Ave., which used to be called Division St. or Line Highway,

is the remnant of such a boundary road marking the line between

Stratford and Fairfield after the exact boundary had been

finally worked out in the 1690's. This road was originally

a six rod road meaning that the right of way for the road

was six rods or 99 feet wide (one rod=l6.5 feet). It begins

as it does today in eastern Redding, where modern Stepney

Rd. intersects with it and proceeds south in as straight a

line as topological features will allow, through the campus

of the University of Bridgeport, ending at the monumental

arch which marks the entrance to Seaside Park. One stretch

of the road was probably never completed and that ran from

the intersection with Flat Rock Rd. in Easton south, to a

point just south of the Merit Parkway bridge. This part of

the straight line route is a very narrow part of the Mill

River valley which was formerly known as a wilderness and

scenic area called Nick's Hole. There was a narrow dirt road

that ran up this through this valley and which has become

part of the modern Park Ave., but this road twisted and turned

following the contours of the valley and not running in a

nice straight line as a good boundary road should. (The section

of road between Flat Rock Rd. and the southern end of North

Park Ave. in Easton was destroyed by the Easton Reservoir.)

The

northern boundary of the town of Fairfield was also marked

by a boundary road which is still an important east-west corridor

for Redding. This road consisted of the modern Church Hill

Rd., Cross Highway, Great Pasture Rd., Fox Run Rd., and Seventy

Acres Rd. Looking at a modem map of Redding, it can easily

be seen that these roads form an almost straight line which

bisects the town from east to west. One section of the boundary

road, east of Fox Run Rd. was obliterated when Mark Twain

built his residence, Stormfield, on it and other sections

twist and turn to negotiate the steep hills which characterize

any east west road in this area, but on the whole the route

is straight and direct, making a clear delineation between

the northern long lots and the area to the north which originally

was not claimed by any of the surrounding towns, hence known

as the Peculiar.

Once

the boundary roads were established, thoughts turned to the

need of gaining access to the interior and northern portions

of the long lot themselves. To meet this need the "upright

highways" were laid out starting in 1692. These roads

derived their name from the fact that they ran in an upright

or north-south direction. In fact, they ran slightly to the

northwest or to the 11 o'clock position on an imaginary clock

face so they were also known as "11 o'clock roads."

One stretch of road in Weston is still called by that name.

The upright highways were to run between the long lots giving

owners access to the northern portions of their lots. As a

result it became common to refer to the highways by the name

of the adjacent long lot owner. Modern roads such as Burr

St, Morehouse Highway, and Tumey Rd. are quaint relics of

this practice.

Like

the boundary roads, the upright highways ran in a perfectly

straight line except where geographical features made this

impossible. Sport Hill Rd., for example, runs through Easton

in a straight line except where it deviates to get around

Beacon Hill, where Silverman's orchard has been establish

(just north of the Easton firehouse). The straightness of

these roads derives from the fact that they were laid out

between perfectly straight long lots which in turn were laid

out on paper, regardless of geographical features, before

they were laid out in fact.

Unlike

the boundary roads, few of the upright highways were ever

completely finished. Of the four upright highways that pass

through Easton into southern Redding, only Sport Hill Rd.,

formerly called Jackson's Highway, was substantially completed,

even though it ended, as it still does, at a rock outcropping

on Stepney Rd. about one mile short of the cross highway boundary

road in Redding. As with many of these early roads, rough

terrain north of this point simply made it impractical to

push the highway further. It was far easier to turn to the

west and go up the valley. When geographical obstacles appeared,

our colonial forebearers, like their descendants today, often

took the path of least resistance.

Another

relatively complete upright highway is Morehouse Highway.

Although a bypass has been constructed just where the road

enters Easton, the old road, complete with its hairpin tums

which enabled the traveler to get to the top of the 90 foot

high hill, can still be seen extending north off of Congress

St. across from the Fairfield branch of this road. From the

top of the hill the old upright highway proceeds in the characterisric

straight line fashion, northward across Center Rd., stopping

at Westport Rd. (Rt.#136). At one time the road extended further

crossing Slady's fruit farm . Now this section of road has

been obliterated but it does pick up north of the farm where

it becomes Bibbins Rd.. Bibbins picks up the straight northward

movement to Cedar Hill Rd. At this point the paved road stops

but a remnant of the old road can be seen passing into the

woods north of Cedar Hill, although it appears now as only

two parallel stone walls with clear ground between them. These

walls stop at the base of a rock escarpment and it is doubtful

if the stretch of road which was to be laid out to the immediate

north of this cliff ever was. A more northern section of Morehouse

Highway was laid out in Redding, however. This appears as

Turney Rd. today, and it runs behind Joel Barlow High School.

Up until the beginning of this century the road ran down to

Rock House Rd. in Eastoh. The old route may still be followed

by tracing the parallel line of stone walls as they run south

of the athletic complex. The northern end of Turney Rd. is

its intersection with Meeker Hill Rd., but originally it ran

north to Church Hill Rd., the eastern end of the cross highway

boundary road. A small portion of this northern terminus survives

as Iris Lane.

From

the incomplete nature of Morehouse Highway we have a clue

as to the manner in which these roads were constructed. The

first section of the upright highways to be laid out were

the southernmost which rose perpendicular to the northern

boundary of the Half Mile Common. The lines which determined

the location of these first road sections were establish by

a surveyor in 1692 and it is probable that the first mile

or so of highway was at least cleared of trees and major obstructions.

Because there was no move to settle in the long lots until

the second quarter of the 18th century, however, the highways

were little used after they were first laid out and they quickly

reverted to the wild. Thus we find that the town had to resurvey

the southern limits of the highways in 1707, 1711, and again

in 1714. Only after 1738, when the town again voted "to

clear the highways that run between the long lots", does

mention of surveying and clearing these roads disappears from

town records, implying that there was sufficient travel on

them after this date to keep the roads relatively clear and

the rights of way sharply defined. As Fairfield settled the

interior northern lands, the roads would have been pushed

farther north, until the areas which were last and lightly

settled were reached and geographical obsticals were encountered,

then, as with Morehouse Highway north of Bibbins, there was

little motivation to push the roads further.

At

the same time that the upright highways were being pushed

northward, the sections of these roads that on paper rested

in Redding were begun and pushed southward. Within a year

of purchasing Lonetown Manor in 1714 and thereby beginning

the settlement of Redding, John Read petitioned the town of

Fairfield to survey the back or northern end of the long lots

and with them the northern terminuses of the upright highways.

It is obvious by this request that Read anticipated growth

in the community which he was helping to establish. Only by

determining clearly and definitely the boundaries of the northern

long lots could he expect to induce settlers to either move

north onto their own lots or purchase a section of the northern

long lots from one of the proprietors and build a family farm

on it. In fact, the narrow nature of these lots made it essential

that their boundaries be established before settlement could

occur because a farm could not be established on a strip of

land to 200 feet wide. Thus the northern portion of neighboring

long lots had to be purchased to put together a workable piece

of farm land.

Settlers

also could not be induced to move to the northern long lots

if those lots were inaccessible. Therefore, after the 1714

survey, the northern portion of the upright highways were

laid out and cleared. Thus, even though Morehouse Highway

was never cleared much beyond Bibbins Rd., the northern sections,

Iris Lane and Turney Rd., were.

In

western Redding this process of highway construction can be

seen even more clearly. To the west of Redding center, the

upright highways which passed between the western long lots,

(today Weston) should have continued up to the western extension

of the cross highway boundary road, namely Seventy Acres and

Fox Run Rds. Only two short section of upright highway, however,

appear to have ever been laid out; Dorothy Rd, along with

part of Wayside Lane which are the northern sections of the

upright highway which survives as Bayberry Lane and White

Birch Dr. in Weston, and Goodsell Rd. which was part of the

highway that survives as Old Hide Rd. and North Ave. In western

Redding, then, only the sections of road which were needed

for convenient movement in that area of town, were constructed

and even then they were never run completely north to the

cross highway boundary road.

Another

factor which severly hampered the construction of the western

upright highways was Devil's Den. This piece of land was virtually

useless except for obtaining fire wood and later in the 19th

century, turning it into charcoal. The land is rocky with

little soil and what soil there is tends to be infertile.

Even worse, the terrain in this area is so uneven that even

the pasturing of cattle is dangerous. As a result, Devil's

Den has remained unused, unsable, and open space down to the

present. The terrain not only removed the motovation to push

the highways through this region, but it also made it nearly

impossible. Therefore, the western upright highways were laid

out and cleared through central Weston and there they stop.

Two northern sections of highway are then constructed solely

for local convenience and not to be able to pass back and

forth to Fairfield village as was the original purpose of

these roads.

For

the sake of completeness, the remaining two upright highways

in the eastern long lots should be traced since they are part

of the basic road structure of Easton, as are Sport Hill Rd.

and Morehouse Highway. Just west of Morehouse Highway is Wilson's

Rd. or Highway. Today the road stops at Beers Rd. but originally,

before the Bridgeport Hydraulic Company closed it in 1914,

it continued southerly into and through Fairfield to Fairfield

Woods Rd., the boundary road for the Half Mile Common. In

a northerly direction Wilson's Rd. passes over Westport Rd.

and becomes Old Sow Rd.. it ends where Old Sow Rd intersects

with Center Rd. and it is doubtful that the highway was ever

pushed further north. The terrain north of Center Rd. is extremely

uneven and the road which has become Black Rock Turnpike follows

a much easier course as it goes up the Aspetuck River valley

and over Jump Hill. A road following the same route as modern

Black Rock Turnpike was established very early; probably in

the mid 18th century since many house of that period are found

along its length and because it is mentioned adn mapped by

the British during the Danbury Raid in 1777. With a convenient

road like this passing up to and over Redding Ridge, there

certainlt was no incentive to push Wilson's road further north

nor to construct a northern section of this highway in Redding.

The

last of the upright highways to be considered here is Burr

St. Very little of the original highway is still in existence,

at least in Easton and Redding. The road enters the western

corner of Easton across Division St. and runs a very short

distance before running into Black Rock Turnpike. At one time,

the section of Black Rock Turnpike that runs north to the

intersection with Wesport Rd. was Burr's Upright Highway.

With the flooding of the Hemlock Reservoir, however, Black

Rock Turnpike had to be moved westward where it took over

the identity of Burr's St.. From Westport Rd., the highway

jogged slightly to the west and then passed through one of

the oldest sections of Easton, Gilbertown, to become Norton

Rd.just north of the Gilbertown Cemetary. Norton Rd. today

degenerates into an impassible dirt track north of Freeborn

Rd., but much of its route northward over the top of the ridge

that separates Easton and Weston, can still be substantially

traced on foot. The highway eventually intersected with Den

Rd. (never paved and now effectively closed to public traffic.).

It then proceeded north to become Greenbush and Sanfordtown

Rds. in Redding stopping only at the cross highway boundary

road at the Redding green. The upright highway solved the

problem of north-south travel, but getting east to west was

another matter. The geography of Easton and Redding in characterized

by a series of north-south running ridges. Thus when the north-south

upright highways were being laid out, they extended along

the ridges. This is one reason why they could be so straight.

There were few elevated areas or large geographical obstructions

along these ridges around which the highways would have to

be rerouted. Going east to west, however, necessitated crossing

these ridges and the intervening river valleys therefore causing

the traveler to be almost constantly climbing precipitous

hills or descending into steep sided valleys. Great Hill on

Cross Highway in Redding is a good example. In traveling east

to west on this road, once you have climbed the 150 feet of

hill on modern Church Hill Rd., you pass over a short level

stretch of road around the intersection with Newtown Turnpike.

Then, as the name implies, you descend the 200 feet of Great

Hill to the Little River valley floor only to start up the

other side as soon as you have crossed the river. Similar

climbs and descents are now waiting for you on Great Pasture

Rd. and Diamond Hill before you finally reach the relatively

level area of Seventy Acres Rd.

A

solution to the problem of east-west travel in northern Fairfield

(travel across the long lots)was partially provided by "cross

highways." These highway obviously did nothing to reduce

the elevations over which the traveler had to climb, but they

did provide a cleared right of way which snaked back and forth,

up and down the hill sides. The series of hairpin turns, such

as the one that still survives on Church Hill Rd., served

to reduce the grade up which your horse had to pull your wagon

or up which you yourself had to walk. In the process of course,

the length of the route that you had to travel was somewhat

increased.

In

1734 the town of Fairfield voted to lay out and construct

the cross highways. This probably coincided with the first

movement of settlers onto the long lots. As with most road

building projects on which the colonial towns embarked, the

vote was not acted upon until 12 years later, a time in which

the pace of settlement in the long lots had increased, thus

increasing the pressure on the town to ease the burden of

cross lot travel. The roads were probably not completed until

1758.

Depending

on how they are counted there were six or seven of these cross

highways built in whole or in part. The first and last respectively

were the Long Lots Rd. to Fairfield Woods Rd. boundary road

and the Cross Highway boundary road in Redding. Both of these

were laid out in the 17th century and were not part of the

planned program of cross highways mentioned above. The identity

of the other cross highways constructed after 1746 are obscure.

Old records frequently refer to the same roads using different

highway numbers. Thus the 4th cross highway for one writer

becomes the 5th cross highway for another. By ignoring numbers

and looking for older roads that ran across most of the town,

perpendicular to the upright highways, the major cross highways

for Easton can be at least tentively identified. (Redding

had only the northern boundary road which still retains the

name Cross Highway.)

The

most southerly of the cross highways apparently run just south

of the present Easton border in Fairfield. In terms of todays

roads, this highway consisted of Jefferson and Congress Streets

running all the way from Burr St.. These roads are not a continuous

line today but rather consist of disconnected segments because

of the intervention of the Merritt Parkway, constructed in

the late 1930's. The next or 2nd cross highway was almost

certainly Beers Rd. which, before the Hemlock Reservoir was

created in 1914, began at Burr St. and proceeded east to its

present starting point at Wilson's Rd. (This section included

what is today Division Rd. on the east side of the reservoir.)

The road then proceeded, as Beers does still, to Sport Hill

Rd. on the other side of which it follows the route of modern

Flat Rock Rd. to Park Ave. Almost equally certain is the 3rd

cross highway which appears today as Westport Rd to Center

Rd. Then Center Rd. to Adams Rd. and along Adams Rd. to North

Park Ave.

The

4th and 5th cross highways, however, are much less certain.

We know that for Weston (the westem long lots.) seven cross

highways were planned and were at least partially laid out

(including the cross highway boundary road in Redding). This

would argue strongly that the same number had been planned

for the eastern long lots. Confusing the issue however are

old documents and land records which tend to call Rock House

Rd. Either the 4th or 5th cross highway. The reason for this

inconsistency is not clear. Possibly two cross highways had

been planned above the line of Westport and Center Rds. and

even partially constructed but had not been used, had fallen

into disrepair and thus forgotten. It is quite possible that

the 4th cross highway was in fact Silver Hill Rd. The section

that would have run to the west of Black Rock Turnpike to

Norton Rd. was never completed and the steep hillside of Flirt

Hill over which it would have to pass is probably the reason

why. In addition, it apparently was never completed to the

east of Sport Hill Rd. to Park Ave. This would leave the line

of Valley Rd. to Staples Rd and Sunny Ridge as a probable

uncompleted 5th cross highway. Rock House Rd. which until

recently ran all the way to Black Rock Turnpike and continued

west as the now disused Den Rd., would then be the 6th cross

highway even though it is frequently refered to in contemporary

documents as the 4th cross highway.

The

confusion here is quite probably the result of the pattern

of settlement in infant Easton. When the cross highways were

being laid out between 1746 and 1758, what is now Easton was

just beginning to be settled. As settlers moved into the area,

they tended to concentrate in communities in the west, Gilbertown

(the area around the Bluebird Inn and Easton swimming pool),

and in the east, the Mill River Valley (under the Easton Reservoir).

There was very little settlement in the northem portions of

this area. Therefore, although the location of the 4th and

5th cross highways were determined, there was little need

to construct them since there were so few people in that area

to use the roads. Even if the rights of way had been cleared

of trees and brush, disuse would have quickly allowed them

to revert to forest. The sections that appear to remain were

quite probably in the area of one or two outlying farms whose

owner found segments of these cross highways useful as access

roads to get cattle back and forth to pasture. Farm access

roads frequently became town roads and were paved in the 20th

century.

This

of course leaves the question of why Rock House Rd as the

6th highway was constructed and maintained. The answer to

this lies in Redding. Redding was settled beginning at least

30 years before Easton. Therefore, by the period when the

cross highways were being built, Redding was a thriving community,

having set herself up as an independent parish as early as

1729. Rock House Rd., running just south of the Redding border,

would have been a convenience to those residents living in

the southern part of the town. As a result the road would

have been used and kept open.

A

quick glance at the roads just outlined on a map will show

that, unlike the upright highways, the cross highways were

far from straight. Again the difficulties of travel from east

to west across the town can be invoked as the explanation.

This difficulty is also reflected in the early specifications

for these roads in that they were originally supposed to be

20 rods (330 feet) wide. This extraordinarily wide right of

way could have been seen as necessary to insure sufficient

land to put in the hairpin turns or switchbacks that were

necessary to lessen the grades of these roads up steep hills.

Another

reason for the wide right of way might be to deal partially

with the problem of erosion and mud. When wide roads were

laid out in most early American communities, it was usually

done to ease drainage problems. The center of the right of

way in these roads always consisted of an 18 to 20 foot area

that was bare dirt, kept free from vegetation by heavy traffic.

During the wet season, however, spring rains turned these

dirt tracks into a sea of mud making passage of horses and

riders difficult and of carriages and wagons almost impossible.

At such times it was possible to travel up the sides of the

right of way where there had been little traffic during the

early parts of the year and thus were not stripped of vegetation

which held the soil and maintained relatively firm footing.

Where

roads ran up or down steep grades the mud season posed a special

problem. Water would run down these steep grades and the steeper

the grade, the faster the water flow and the greater the erosion

of the roadbed. In many early hill roads deep gullies were

formed after even a few years of existence. In some remaining

remnants of the early steep roads, which have not been recently

graded or paved, entrenching has lowered the roadbed eight

to ten feet below the old ground surface level. Building hairpin

turns on these roads reduced the grade and consequently the

rate of water run off, but it did not completely stop erosion.

Vegetation along the sides of the right of way would have

further slowed water run off and retarded erosion. Regardless

these measures were only partially successful as existing

relies of these old roads demonstrate. With respect to the

cross highways, the original intentions of the road planners

may have been to deal with these problems by employing the

extraordinarily wide right of way, but expediency, or maybe

it was just the cost of acquiring the extra land, prevailed

and t 2 years after the first proposal, the road width was

reduced to the standard six rods (99 feet).

As

should be apparent from the above discussion, traveling the

colonial and early American road system was not easy, nor

was it fast. In addition to the problems of the mud season,

there were numerous others. Although the right of way of any

of these roads were supposed to be cleared of obstructions,

they rarely were. If a rock was too large to be removed easily

from the traffic path by an ox team, it was left and traffic

was expected to maneuver around it, or, if the rock was low

enough, to go over it endangering wheels and axles. Trees

were cut down but stumps were rarely removed. They were left

to rot and again traffic had to maneuver around them. If the

traffic on any given stretch of road was insufficient to keep

the vegetation down, brush and small trees quickly invaded

the right of way. Farmers living off of these roads were expected

to keep them clear of obstructions, but the town records are

filled with votes to deal with highways that had become impassible

and which need to be maintained.

In

addition to hills that had to be climbed and streams that

had to be forded, swamps also had to be crossed. If the swamp

was small nothing was done and traffic was expected to wade

through it. Occasionally there was an attempt to firm up the

roadbed by pitching rocks into the slime along the right of

way or by setting sections of logs side by side across the

soft areas, but with the weight of passing traffic, the rocks

frequently sank too deep to be useful and logs quickly rotted

and broke through. If the swamp was large, an attempt was

made to build an elevated section or causeway across it by

using rocks and dirt to build up the right of way. This is

in part the origin of the term highway. A relic of this technique

can still be seen in the small segment of old Stepney Rd.(Rt#59)

in Easton which passed immediately to the east of the Baptist

church. The elevated roadway extends for several yards out

into the swamp. It apparently was insufficient and the town

voted to simply go around the edge of the swamp, an alternative

frequently employed by other early American road builders

when faced with a swamp.

Not

only natural factors but humans also impeded movement along

early roadways. Farmers frequently looked upon the roads that

passed through or adjacent to their farms as being extensions

of their lands. Thus the grass growing along the sides and

into the right of way was a resource to be utilized by his

cattle. Negotiating one's way through a herd of grazing cows

is a common annoyance mentioned by early travelers. Farmers

even went so far as to erect gates across the roadway so that

their cattle did not wander too far away. Town meetings down

to the late 19th century were constantly issuing instructions

to their highway surveyor and haywards to remove such obstacles.

Is

it any wonder, with all of these inconveniences, why people

who traveled during these early periods, preferred traveling

by water and if water transportation was not possible, they

preferred to stay home. The state of the roads was one reason

why inland communities tended to be close. To run from Easton

or Redding into Bridgeport or Danbury was not a 20 minute

trip as it is with paved roads and high performance automobiles,

but rather a several hour to half a day expedition, depending

on from where you started. Thus trips to town were infrequent

and done only for pressing business or to pick up such goods

as could not be produced in the community or on the farm.

Needs for social contact and entertainment were satisfied

within the neighborhood and this created a closeness which

has become one of the notable characteristics of colonial

and early American life.

As

imperfect as the roads were and as difficult as travel over

them was, the grid of upright and cross highways was an important

one. At its most basic, this road structure allowed access

to the interior lands that would become Easton and Redding

and thereby encouraged settlement, in the same way that paved

roads and automobiles today have turned these towns into suburbs.

In addition, they allowed movement between neighborhoods within

these areas as well as movement between outlying farms and

the meeting house, general store, and tavern that were so

important to the isolated farmer. In a very real sense they

made these outlying farms possible and road crossings often

determined where whole neighborhoods would develop.

In

a broader sense this early road structure determined the present

pattern of roads in these towns as well as their traffic flows

and patterns of modem residential development. As Easton and

Redding moved into the 20th century, the old upright and cross

highways were the first to become paved and thus they became

the major arteries into and out of town, as well as between

areas within the towns. These early paved roads constitute

the basic road structure of this area. This basic structure

would be modified as old farm access roads became paved to

give access to more remote areas of town. More recently it

would be modified by new subdivision roads which follow a

map line set up to most efficiently develop a parcel of land.

But the basic structure still remains and therefore to understand

the interactions within the towns of Easton and Redding as

well as their development, it is necessary to understand the

patterns and nature of the highways that were first built

in these areas and called upright and cross highway.

"Turnpikes

of Easton and Redding" by Daniel Cruson

As

the 18th century drew to a close, the first stirring of the

Industrial Revolution were being felt both in Europe and the

United States. One of the prerequisites for this industrial

development was a transportation system which provided for

easy and inexpensive movement of raw material to mills and

factories and the movement of finished products out to markets

at home and abroad. In coastal areas, where there was ready

access to water, adequate transportation was much less of

a problem than it was in interior areas like Easton and Redding

where there was neither direct access to the ocean nor any

navigable rivers down which products could be floated by barge

or river boat. The interior, therefore, was forced to rely

on overland transportation and, until the development of railroads

about the middle of the 19th century, this meant reliance

on wagons and the roads over which they had to pass. The state

of the roads in this area, however, was very poor. Overland

transportation even for a single horse and rider, was difficult

and, at times such as the wet spring season, nearly impossible

as dirt roadways dissolved into a sea of mud. This was true

not only in central Fairfield County but in the entire nation

as well.

A

major problem that faced the United States in the 1790's,

then, was how to improve the state of the Nations roads. Road

construction and repair was a very expensive process, and

the federal government had little in the way of money, especially

since direct taxation, such as the Income Tax, would not appear

until the 20th century. In addition there was a strong feeling

among most citizens that the federal Government should stay

out of the road building business. The answer to this dilemma

was to turn the business of road construction and repair over

to private individuals and the most efficient means of doing

this was through incorporation. Thus began an economic period

referred to by historians as the Turnpike Movement.

Individual

states, such as Connecticut, had the right to charter and

thus create corporations. A corporation is a legal entity

which is entitled to sell shares of ownership in itself, called

stocks, in order to raise the money necessary to set itself

up in business. Corporations had occasionally been chartered

for purposes of colonization and various manufacturing processes

in the early colonial period. With the formation of state

governments in the wake of the Revolution, however, the number

of incorporations increased until, by the decade of the 1790's,

this growth became dramatic, especially as corporations were

applied to transportation and the construction, repair, and

improvement of roads and bridges. One type of corporation

that was specifically set up to construct or repair a road

then was the turnpike company.

To

form a turnpike in Connecticut, as in most other states, it

was first necessary for a group of men to draw up a petition

to be submitted to the state legislature asking for the privilege

of incorporation and proposing a route along which the road

would be constructed or, in the case of an already existing

road, improved. Once incorporation was granted, the founders

of the turnpike corporation would meet, elect officers, and

determine how much money was going to be needed to construct

and maintain or improve the roadway. Once this was determined,

the corporation would issue and sell stock. By doing this

the corporation sells small pieces of itself. The money that

is raised by this process is then put toward the acquisition

of land along the proposed route, if a road was not already

in existence, and toward the actual construction or improvement

of the roadbed.

It

is important to remember that the turnpike company was a business

venture and that the purchasers of these early company's stock

expected to receive dividends, a share of the company's profits,

in return for their stock purchase. But where was the money

to come from that would constitute the company's profit? In

the corporation charter, the turnpike company was given the

right to charge a fee or toll to all of those who would be

using the road. The toll rate was carefully controlled by

the state legislature and was to be collected at a tollgate

placed at a convenient location or locations along the length

of the road. The tollgate usually consisted of a small house

in which the toll taker could take refuge in inclement weather,

and a long pole or pike that could be rotated horizontally

on a post to block the road until the toll was paid, and then

rotated out of the way to allow the passage of the toll paid

traffic. It is the turnpikes which gave these roads their

names.

The

tolls which supplied profits and thus dividends, usually made

the formation of turnpike companies a very attractive venture

in areas where there was a substantial volume of traffic passing

in and out of a region. This accounts for the large number

of turnpike companies that were formed in the 1790's and through

the first three decades of the 19th century. By 1800 there

were 219 turnpikes and bridge companies in the U.S. but only

six manufacturing concerns were organized as corporations.

This ratio of manufacturing to transportation corporations

would be reversed by the second quarter of the 19th century

but the figures for the early years of this century clearly

show how profitable and popular the turnpike movement was.

Entrusting road building to private hands rather than to the

government was clearly successful, at least in the early stages

of the Industrial Revolution.

What

was true for the nation, was no less true for the state and

for the towns of Easton and Redding. The basic structure of

roads in these towns had been created by the system of upright

and cross highways constructed in the late 17th and early

18th centuries, but these highways had been laid out first

on paper without regard for the actual patterns of traffic

created by local geography nor the traffic patterns that developed

as the communities grew and prospered. Modifications and improvement

of this basic road structure, then, would be accomplished

by turnpike companies as they perceived the need for new traffic

patterns or improvements to old ones, and acted on these needs

for their own profit.

A

good example of one of these local transportation companies

is the Stratfield and Weston Turnpike Company. [note: Weston

until 1845 included Easton] Chartered as the result of a petition

to the General Assembly in 1797, this company was permitted

to issue stock and with the proceeds from this stock sale

they were to repair and modernize a stretch of road that began

"at the foot of the hill...before the Baptist meeting

house, and extend north in Jackson's Upright Highway so called

until it comes to the Cross Highway about 25 rods [about 400

feet] above the dwelling house of David Silliman" in

Easton. This road today is the section of Sport Hill Road

that runs from the Baptist church, which still stands on the

hill in Stratfield just below Fairfield Woods Road, north

to Rock House Road in Easton. Apparently this stretch of road

was in almost impassible condition and the formation of the

Stratfield and Weston Turnpike Co. was a means whereby the

road could be made fully usable without having those repair

become the concern of the towns involved and without having

to raise taxes to pay for it.

Also

by the provision of their charter, this company was entitled

to set up a toll house and turnpike and to collect tolls according

to a fee schedule that was established by the General Assembly.

The toll house and turnpike were set up at the base of what

is today Sport Hill Road, across from Jefferson Street, where

entrance to the General Electric corporate headquarters driveway

is situated. There it remained for 89 years until the company's

charter was repealed and the road made free in 1886.

The

fees collected at this tollgate were very carefully regulated

since turnpikes were seen as a type of natural monopoly over

which the traveler and resident had no control. For the Stratfield

and Weston Turnpike a fee of 6.2 cents could be collected

for every loaded wagon (half that fee a the wagon was empty),

4 cents for a loaded one horse sleigh, 12.5 cents for a pleasure

carriage of any kind, 4 cents for a man on horseback, and

1 cent for every sheep or pig that was herded through the

tollgate. A penny of course was worth more during this period

than it is today. According to government statistics for consumer

prices at various time in our history, one penny was about

7.5 times more valuable in 1800 than now. Therefore in today's

money every sheep or pig would cost 7.5 cents, every man on

horseback would be charged 30 cents and any pleasure carriage

would have to pay almost a dollar for the privilege of driving

up Sport Hill Road into Easton along a fully modern gravel

road.

Although

these toll rates might seem burdensome, especially for anyone

who used the road regularly to pass back and forth between

Easton and Fairfield or Bridgeport, there were exceptional

circumstances under which the tolls did not have to be paid.

These were also carefully spelled out by the General Assembly.

Exempt were all persons going to or returning from a funeral,

public worship, or a saw or grist mill. In addition, "

all officers or soldiers on days of military exercise on command

who must necessarily pass through...the gate," were exempt,

as were all residents who "live near the place where

the toll gate is erected, whose necessary daily calling requires

their passing the gate.”

The

General Assembly also regulated the way in which revenues

from tolls would be disbursed. As with any business, a portion

of these revenues would be used to cover the cost of repairs

and maintenance of the roadbed and payment of a toll taker.

In a modern corporation, profits, their revenues after all

costs are deducted, are then distributed to the stock holders

as dividends in proportion to the number of shares of stock

owned. The Stratfield and Weston Turnpike Co., however, was

only allowed to distribute an amount of profit to each stockholder

equal to 12% per year of the total amount that the stockholder

had paid for his stock. All money that was left after these

dividend payments had been made were to be used to pay back

the money that the company had collected from its stockholders

as a result of the original stock sales. In this, the money

from stock sales was being treated as a loan rather than a

true investment in the company. Ideally the amount of money

that the stockholder had made available to the corporation,

would be slowly returned to the stockholder until he was entirely

paid back. Then there would no longer be a need to collect

tolls and the road would become free. Since we know that the

Stratfield and Weston Turnpike Co. continued to collect tolls

until 1886 when Fairfield County made all of its turnpikes

free, it is fair to assume that the company never had large

enough revenues to pay back its stockholders, although the

enterprise must have been fairly profitable or it would not

have survived as a corporation for almost 90 years.

Older

than the Stratfield and Weston turnpike Co. by about six months

was the Fairfield, Weston, and Reading Turnpike Co. which

received its charter in May of 1797. This company improved

and maintained a section of road that ran from the home of

Samuel Wakeman Jr. in Easton, across Redding Ridge to the

meeting house in Bethel, which was then part of Danbury. The

Samuel Wakeman house is still in existence and it sits on

route #58, opposite the mouth of Freeborn Road. The turnpike

extended from that point north along route #58 to Sunset Hill

Road. It then went north along Sunset Hill and over Hoyt's

Hill into Bethel as far as the Congregational church. (The

section of modern route #58 which runs from Sunset Hill Road

to Putnam Park, is a new stretch of road that was constructed

around the turn of this century to facilitate access to the

park.)

The

tollgate for this turnpike was located " at the house

of Samuel Thorp," which was apparently located just north

of Jump Hill, on the flat stretch of road which lies just

south of the Redding border. Having their tollgate so far

south on the road posed a revenue problem, however, since

many people were using just the northern sections of this

road and thus not paying tolls for the use of the road. This

problem materialized very early in the company's history,

for in 1798, a little over a year after their formation, they

petitioned the legislature and were granted permission to

establish a tollgate on the northern portion of the road provided

that someone traveling the full length of the road would only

have to pay at one tollgate and not at both. Unfortunately

the location of this upper tollgate was never mentioned in

the legislative records and is therefore unknown. It continued

to function, however, the road was declared free in 1834.

The entire road became free when the company's charter was

repealed in 1838.

Another

turnpike was created in 1832 whose history was to become closely

tied to the Fairfield, Weston, and Redding Co.; The Black

Rock and Weston Turnpike. The company that was chartered to

construct and improve this road was permitted to operate from

Black Rock Harbor northwesterly to a point just north of today's

Westport Road (route #136). The purpose for constructing this

road was obviously to facilitate the movement of farm produce

and other small locally produced goods to the harbor for transshipment

by water to markets in places like New York City and the South.

The road became an even more valuable link to the coast when

it was connected to the Fairfield, Weston,and Redding Turnpike

by a short stretch of road running from Westport Road to Freeborn

Road creating what is still known as Black Rock Turnpike running

from Bethel to Long Island Sound. The road was made entirely

free when the Black Rock and Weston Turnpike Co. was dissolved

in 1851.

Among

the other roads in this area which began as turnpikes are

Newtown Turnpike and Hopewell Woods Road in Redding. These

roads are what remains of the Newtown and Norwalk Turnpike

which was chartered in 1829 to run from the " foot of

Main Street in Newtown, passing near the Episcopal church

in Redding, through the westerly part of Weston, (and) ultimately

to the great bridge in Norwalk at the head of Norwalk Harbor."

Again the motive for building this road was to facilitate

the movement of goods from the interior to the coast. By 1841,

the northern portion of this road running through Redding

and Newtown was made free and tolls were dropped on the rest

of the road by 1851.

The

Fairfield County Turnpike, which ran through both Easton and

Redding, had a relatively short life and ran along a very

confusing route. It was chartered in May of 1834 and its charter

was repealed in 1848 after two changes in location had been

approved in 1836 and 1837. The final route of this turnpike

was supposed to have run from the northern end of the Black

Rock and Weston Turnpike (where routes 58 and 136 intersect

today) across Easton, through eastern Redding to the southwesterly

portion of Newtown, and passing ultimately into Brookfield

ending at "Meeker's Mill." In terms of modern roads,

this turnpike appears to have passed up Westport Road (route#136)

to Staples Road, up Staples to Valley Road, and then followed

Valley Road through Poverty Hollow in Redding and Newtown,

turning down Flat Swamp Road and passing through Dodgingtown.

A

longer lived turnpike, but one with an equally unclear route

was the Weston Turnpike. It was chartered in May of 1828 and

only became a free road when Fairfield County cleared itself

of all turnpikes on March 24, 1886. The route is described

as running "from Philo Lyons to the Black Rock Road in

Fairfield with a branch from Fairfield to the Academy in Weston."

The location of Philo Lyons house is not known precisely but

it probably stood on Morehouse Highway about one mile north

of the junction with Beers Road. From this point on Morehouse

Highway, the turnpike probably ran south to Beers Road, then

west along Beers beyond Wilson Road and under what is now

the Hemlock Reservoir, to end at Black Rock Turnpike. The

section of this turnpike which ran to the west of Wilson Road

was closed and abandoned when the Bridgeport Hydraulic Company

built the reservoir in 1914. The "branch from Fairfield

to the Academy in Weston," was probably Wilson Road from

Beers to Westport Road, to the Staples Academy building which

still exists as part of the parish hall for the Congregational

Church.

A

turnpike about which we have very little information is the

Simpaug Turnpike in northwestern Redding. We do know that

a company was chartered to build this road in 1832. We do

not know when the road was made free but it must have happened

by 1886 when the County abolished its turnpikes. Modern road

names suggest that the turnpike started in the business section

of Bethel and ran southwesterly along what is now route#53

and Side Cut Road to the village of West Redding. From that

point it appears to run along the railroad tracks south and

west to the Topstone area where today it swings out and joins

the Ethan Allen Highway (route #7). It is not known if the

turnpike ever ran beyond its intersection with route#7. It

is also not certain where the name comes from unless it refers

to the Simpaug ponds which lie near its point of origin in

Bethel.

The

road that started as the Branch Turnpike is still an important

east-west corridor through Easton. The company that built

this road was incorporated in May of 1831 and the road itself

extended from Bennett's Bridge across the Housatonic River

(just north of the Rochambeau Bridge which carries route#84

traffic across the same river today.), through south and east

Newtown, Monroe, Easton, and Fairfield, ending in Westport.

Today in Easton this road is Stepney Road (route #59) running

from the village of Upper Stepney to the Easton Rotary (The

four way stop below Union Cemetary and the Baptist Church.)

From the Rotary it becomes Westport Road (route #136) and

runs southwesterly to a point just south of the village of

Westport. This road became free when its charter was repealed

in 1851, 20 years after it had been founded.

One

further turnpike must be considered for the sake of completeness

of this treatment if not for the importance of the road itself;

the Sherman and Redding Turnpike. The company which built

this road was chartered in 1834 and the road ran from the

town of Sherman to either the Newtown and Norwalk Turnpike

in Redding or to the Northfield Turnpike in Weston. According

to Frederick Woods, who wrote the definitive book on the turnpikes

of New England, "it is clear that the plans were carried

out, but it is impossible today to pick out the location."

According to a petition which was filed with the General Assembly

in 1846, the turnpike was "never demanded by public necessity

or convenience and that for six years it had been wholly and

entirely abandoned, and consequently impassible and useless."

From this it would appear that the turnpike had a life span

of less than six years. All that remains of the road today

is a short stretch of road in central Redding which is still

called Sherman Turnpike, running from the Redding Green south

to Newtown Turnpike. Other sections of this turnpike may still

be in existence under other names but since its route north

of the Redding Green is unknown it is impossible to be sure

that any of these other roads lie along the old Sherman Turnpike.

The

Sherman Turnpike was an apparent financial failure which underscores

an important aspect of the entire Turnpike Movement; turnpikes

were a business, supported by private financiers and dedicated

to improving overland transportation without resorting to

federal government control and expenditures nor requiring

tax revenues. As with any businesses, some were failures like

the Sherman Turnpike and others were highly successful such

as the Branch Turnpike which became Westport Road and the

Stratfield and Weston Turnpike which became Sport Hill Road.

The failures had little impact on this area beyond supplying

an occasional place name or reference in an old land deed.

The successes, however, because they served a necessary function

such as getting goods and people from the interior to the

coast, or supplied a public convenience such as getting people

across town easily, survived and became improvements and modifications

of the basic road structure in this area. The Turnpike Movement

was the most important phase in the development of local roads

and transportation between the establishment of the basic

road structure with the upright and cross Highways of the

late 17th century and the concerted push during the early

20th century by the towns themselves to pave all of their

roads. The turnpikes also stand as one of the highest expressions

of the American ideal that the most desirable way to accomplish

something is not through government effort and expenditure

but rather through the exercise of Capitalism and private

enterprise.

| |

|

|

| |

Redding

and Easton

by Daniel Cruson

*Great Photos of Early Redding

|

|

The

Old Turnpike thru Georgetown- by Wilbur F. Thompson. For

many years after the first settlement of our state, the roadways

connecting the towns were very poor. Many were mere "bridle

paths," others were Indian Trails widened into "Cart Paths."

One of these was the Indian Trail leading up from the Sound,

at what is now known as Calf Pasture Beach, through the section

now known as Georgetown, into what is now the city of Danbury.

It was over this trail that the eight families left Norwalk

in 1684, to found the new town of Danbury. And for many years

this trail, widened into a cart path, was the only connecting

link between the two places.

As

the town of Danbury grew, the need of a better means of transportation

became apparent. A survey was made and a new highway was opened

up. From Danbury the turnpike followed South Street to what

is now Reservoir Road, to Long Ridge Road, into West Redding,

up over the Umpawaug Hill, Redding, through what is now Boston

district and Georgetown, and on to Norwalk. The right of way

was six rods wide. It was known as the "great road" from Danbury

to Norwalk.

[On

South Street, Danbury, there is still a mile-stone bearing

the date of 1787, "68 miles to New York, 67 miles to Hartford."]

In

1723 Nathan Gold (Gould) and Peter Burr of the town of Fairfield

sold to Samuel Couch and Thomas Nash, of the same town, one

hundred acres of land in the Parish of Redding, town of Fairfield,

"said land lyeing on both sides of the great road, that leads

from Norwalke to Danbury," showing that the road was in use

at that date.

In

1792 the town of Redding voted to reduce the width of the

Danbury and Norwalk road, in Redding, to four rods.

In

1795 the "Norwalk and Danbury Turnpike Company" was formed.

The company was incorporated for the purpose of "making and

keeping in repair the great road from Danbury to Norwalk -

from Simpaug Brook, Bethel, to Belden's Bridge, Norwalk (now

Wilton) and to erect gates and collect tolls for the maintenance

of the same." Toll gates were erected at intervals along the

road. One was north of where Connery Brother's store once

stood in Georgetown (likely about where Georgetown Auto Body

is located). This was the only road of consequence in the

area and soon became the Post Road.

Proof

of its importance is indicated by the location selected as

Redding's first Post Office. On December 22, 1810, Redding's

first Post Office was established with Billy Comstock as Postmaster,

keeping office in his house which was located at what is today

the corner of Umpawaug and Route 107. Across the street was

a tavern which was also the place where horses were changed

and fresh horses put on. The tavern serviced the stage coaches

as they passed through Redding to meet the Danbury and Norwalk

stage. This location was known as Boston Corners, and for

some time Darling's Corners as well. Later the horses were

changed in Georgetown at Godfrey's store on Old Mill Road.

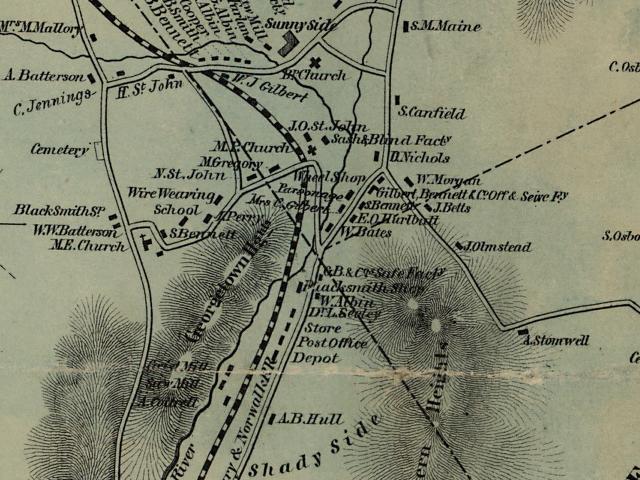

Clark's

Map of 1856 showing Old Mill Road on the right. You'll notice

Old Mill

Road was far more popular than Route 7 (road on the left)

at that time period.

As

the towns grew and the intervening section became thickly

settled, the "Old Turnpike" became a congested thorough-fare.

Historian Wilbur F. Thompson explained that his grandfather,

Aaron Bennett, said "in his boyhood days (1818) there was

an unending procession of great canvas-topped freight wagons,

stage coaches, slow-moving ox carts. Travelers on horseback

and on "Shanks Mares" (pedestrians) passing both ways night

and day." At about this date the Sugar Hollow Turnpike

was opened up. Starting at Belden's Bridge, Norwalk (now Wilton)

on the west side of the Norwalk River, up through Georgetown

and into the Sugar Hollow Valley, along the course of the

river, through the town of Ridgefield, and into the western

side of Danbury. This is now [Route 7] the state road from

Danbury to Norwalk.

Back

to TOP | Back to Redding

Section | Back to Georgetown

Section

|

|